Chapter 1: Globalization

2nd Edition, Published 2026. Jennifer Brogee, editor. See Contributing Authors section for original authors. License:  Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike CC BY-NC-SA

Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike CC BY-NC-SA

The sun sets over Battambang, Cambodia. Photo by Jennifer Brogee.

Four Stories of Globalization

We begin this chapter with four stories from around the world.

United Arab Emirates

Figure 1.1 is a screenshot from a Dubai government website that promotes business and tourism in Dubai.See “Dubai for Business,” Government of Dubai: Department of Tourism and Commerce Marketing, accessed July 27, 2011, http://www.dubaitourism.ae/definitely-dubai/dubai-business. It details many different ways in which Dubai is a desirable place for businesses to locate. For example, the website contains the following:

Figure 1.1

Pro-Business Environment

Dubai offers incoming business all the advantages of a highly developed economy. Its infrastructure and services match the highest international standards, facilitating efficiency, quality, and service. Among the benefits are:

Free enterprise system.

Highly developed transport infrastructure.

State-of-the-art telecommunications.

Sophisticated financial and services sector.

Top international exhibition and conference venue.

High quality office and residential accommodation.

Reliable power, utilities, etc.

First class hotels, hospitals, schools, and shops.

Cosmopolitan lifestyle.

The website goes on to talk about benefits such as the absence of corporate or income taxes, the absence of trade barriers, competitive labor and energy costs, and so on.

Vietnam

The following is an extract from the Taipei Times, April 9, 2007.

Compal Eyes Vietnam for Factory

Compal Electronics Inc, the world’s second-largest laptop contract computer maker, is considering building a new factory in Vietnam.

Compal could join the growing number of Taiwanese electronic companies investing in Vietnam—such as component maker Hon Hai Precision Industry Co—in pursuit of more cost-effective manufacturing sites outside China.

[…]

Compal forecast last month that its shipments of notebook computers would expand around 38 percent to 20 million units this year, from 14.5 million units last year. The company currently makes 24 million computers a year at its factories in Kunshan, China.

Compal, which supplies computers to Dell Inc and other big brands, could lack the capacity to match customers’ demand next year if its shipments increase any faster,…

Lower wages and better preferential tax breaks promised by the Vietnamese government could be prime factors for choosing Vietnam, Compal chairman Rock Hsu said earlier this year.

[…] See “Compal Eyes Vietnam for Factory, Taipei Times, April 9, 2007, accessed June 28, 2011, http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/biz/print/2007/04/09/2003355949. We have corrected a minor grammatical error in the article.

Niger

In Niger, West Africa, the World Bank is funding a $300 million project to improve education: “The Basic Education Project for Niger’s objectives are: (i) to increase enrollment and completion in basic education programs and (ii) to improve management at all levels by improving the use of existing resources, focusing on rural areas to achieve greater equity and poverty reduction in the medium to long term.” For more details, see World Bank, “Basic Education Project” World Bank, accessed June 28, 2011, http://web.worldbank.org/external/projects/main?pagePK=64283627&piPK=73230&theSitePK=40941&menuPK=228424&Projectid=P061209. The World Bank website explains that the goals of the project are to improve access to primary education (including adult literacy), improve the quality of primary and secondary education, and improve the management capability of the Ministry of Education.

United States

President Obama recently established the President’s Council on Jobs and Competitiveness, which is charged, among other things, with reporting “directly to the President on the design, implementation, and evaluation of policies to promote the growth of the American economy, enhance the skills and education of Americans, maintain a stable and sound financial and banking system, create stable jobs for American workers, and improve the long term prosperity and competitiveness of the American people.” See “President’s Council on Jobs and Competitiveness: About the Council,” accessed July 27, 2011, http://www.whitehouse.gov/administration/advisory-boards/jobs-council/about. In his concern with competitiveness, President Obama follows directly in the footsteps of President George W. Bush, who, in 2006, established the American Competitiveness Initiative to Encourage American Innovation and Strengthen Our Nation’s Ability to Compete in the Global Economy. George W. Bush, “State of the Union: American Competitiveness Initiative,” White House Office of Communications, January 31, 2006, accessed June 28, 2011, http://www2.ed.gov/about/inits/ed/competitiveness/sou-competitiveness.pdf.

At first reading, these five stories seem to have little to do with each other. There is no obvious connection between the actions of the World Bank in Niger and Taiwanese computer manufacturers in Vietnam or the marketing of Dubai. Yet they are indeed all connected. Think for a moment about the consequences of the following:

A superior business environment in Dubai

Improved education in Niger

A new factory opening in Vietnam

An improved banking system in the United States

Of course, each story has many different implications. But they have something fundamental in common: every single one of them will increase the real gross domestic product (real GDP) of the country in question. They all therefore shed light on one of the most fundamental questions in macroeconomics:

What determines a country’s real GDP?

As we tackle this question, we will see that it is indeed connected to our stories of Dubai, Niger, Vietnam, and the United States.

Our stories have something else in common as well. In each case, they concern not only the country in isolation but also how it interacts with the rest of the world. The funds for Niger’s education program are coming from other countries (via the World Bank). The US policy is designed to ensure that America is “leading the global competition that will determine our success in the 21st century.” “Obama Presses for an Economy in ‘Overdrive’: Will Jobs Soon Follow?,” PBS NewsHour, January 21, 2011, accessed August 22, 2011, http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/business/jan-june11/obamabusiness_01-21.html. Dubai is trying to attract investment from other countries. The factory in Vietnam is being built so that a Taiwanese company can supply other manufacturers throughout the world.

Road Map

Real GDP is the broadest measure that we have of the amount of economic activity in an economy. In this chapter, we investigate the supply of real GDP in an economy. Firms in an economy create goods and services by transforming inputs into outputs. For example, think about the manufacture of a pizza. It begins with a recipe—a set of instructions. A chef following this recipe might require 30 minutes of labor time to make the dough and assemble the toppings and then might need 15 minutes use of a pizza oven to cook the pizza. The inputs here are as follows: the pizza oven, the labor time, the skills of the chef, and the recipe. Given 15 minutes of capital time, 30 minutes of labor time, a skilled chef, and the instructions, we can make one pizza.

In macroeconomics, we work with the analogous idea that explains how the total production in an economy depends on the available inputs. We first explain the relationship between the available inputs in the economy and the amount of real GDP that the economy can produce. Then we look at all the individual inputs in turn. If we can explain what determines the amount of each input in an economy and if we know the link from inputs to real GDP, then we can determine the level of real GDP. Finally, we look at a technique that allows us to quantify the relationship between inputs and output. Specifically, we look at how increases in different inputs translate into increases in overall GDP. Using this technique, we can see which inputs are particularly important.

1.1 The Production of Real GDP

Learning Objectives

What determines the production capabilities of an economy?

What is the marginal product of an input?

How is competitiveness related to the aggregate production function?

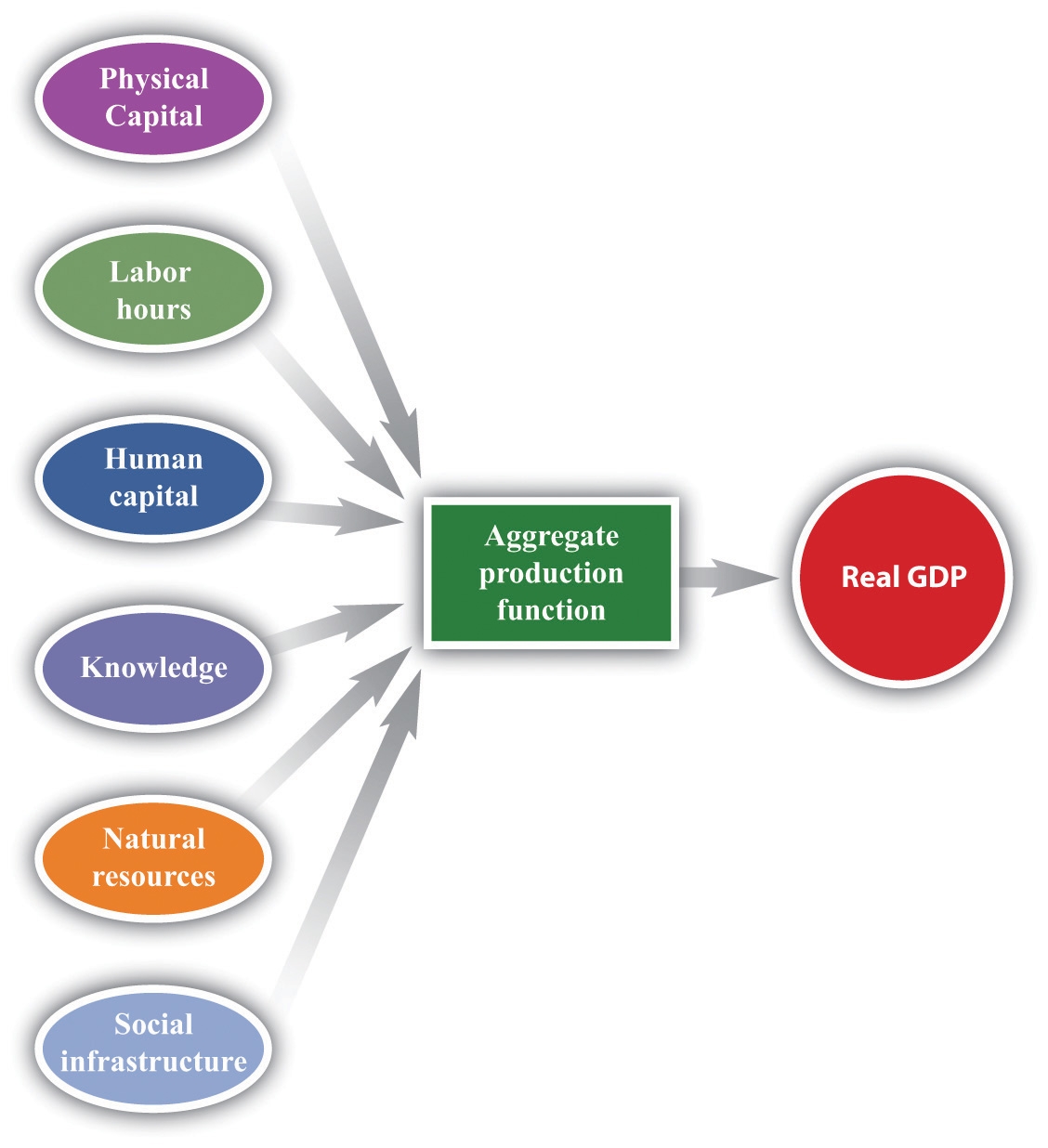

Economists analyze production in an economy by analogy to the production of output by a firm. Just as a firm takes inputs and transforms them into output, so also does the economy as a whole. We summarize the production capabilities of an economy with an aggregate production function — a combination of an economy’s physical capital stock, labor hours, human capital, knowledge, natural resources, and social infrastructure that produces output (real GDP).

The Aggregate Production Function

Toolkit: Section 16.15 "The Aggregate Production Function" — https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_macroeconomics-theory-through-applications/coopermacro-ch16_s15#coopermacro-ch16_s15

The aggregate production function describes how aggregate output (real gross domestic product [real GDP] — a measure of production that has been corrected for any changes in overall prices) in an economy depends on available inputs. The most important inputs are as follows:

Physical capital: machines, production facilities, and so forth used in production

Labor: the number of hours that are worked in the entire economy

Human capital: the skills and education embodied in the work force of the economy

Knowledge: the blueprints that describe the production process

Natural resources: oil, coal, and other mineral deposits; agricultural and forest lands; and other resources

Social infrastructure: the general business climate, the legal environment, and any relevant features of the culture

Output increases whenever there is an increase in one of these inputs, all else being the same.

Definitions and brief notes embedded in the text:

Physical capital: goods—such as factory buildings, machinery, and trucks—used in production. Capital goods are used in the production of other goods and are long lasting.

Capital stock: the total amount of physical capital in an economy (includes public infrastructure).

Labor hours: the total number of hours worked in an economy (number employed × average hours worked).

Human capital: skills and training embodied within workers (education, on-the-job training).

Knowledge: information in books, software, blueprints; inventions and innovations.

Natural resources: land; oil, coal, minerals; agricultural land.

Social infrastructure: legal, political, and cultural frameworks (property rights, rule of law, corruption levels).

We show the production function schematically in Figure 5.2 "The Aggregate Production Function".

Figure 1.2 The Aggregate Production Function

The aggregate production function combines an economy’s physical capital stock, labor hours, human capital, knowledge, natural resources, and social infrastructure to produce output (real GDP).

The idea of the production function is simple: if we put more in, we get more out.

With more physical capital, we can produce more output.

With more labor hours, we can produce more output.

With more education and skills, we can produce more output.

With more knowledge, we can produce more output.

With more natural resources, we can produce more output (though resources may deplete).

With better institutions, we can produce more output.

Marginal product — the extra output obtained from one more unit of an input, holding all other inputs fixed — applies to each input (marginal product of capital, labor, etc.).

Physical capital and labor hours are relatively straightforward to understand and measure. Human capital, knowledge, social infrastructure, and natural resources are much harder to quantify; researchers use proxies (educational attainment, R&D spending, corruption surveys, etc.). Natural resource measurement is especially tricky since untapped reserves contribute to wealth but not current production.

Note on raw materials: the aggregate production function measures value added (output minus raw material inputs) to avoid double counting. Reserves of natural resources are not counted as raw materials; the output of mining is the value of resources extracted.

Globalization and Competitiveness: A First Look

Over recent decades, technological developments have reduced the cost of moving physical goods and information globally. Examples:

Fresh produce flown across continents

Financial transactions across time zones

Travel for work and leisure

Remote professional services

These are examples of globalization — the ever increasing interdependence among countries in the areas of trade, information, politics, finance, labor, institutions, and more.

One consequence is intensified competition among firms across countries. Firms now compete globally for customers and for inputs (capital and skilled labor). Competitiveness refers to the ability of an economy to attract physical capital.

Important nuance: national “competition” differs from firm competition. Countries do not necessarily win only at the expense of others. For example, South Korea producing better computers may make life harder for some US firms but raises world output and incomes, benefiting many parties including US consumers.

Countries compete to attract inputs (capital, skilled labor). Movements of capital and labor affect production functions and real GDP. Competition for capital does not directly determine the number of jobs at the national level (employment levels are determined by labor-market mechanisms described in other chapters), though closures can harm individual workers.

Key Takeaways

The production capabilities of an economy are described by the aggregate production function: capital, labor, technology, human capital, knowledge, natural resources, and social infrastructure combined produce real GDP.

Marginal product: extra real GDP from an extra unit of input, holding others constant.

Competitiveness: an economy’s ability to attract inputs (especially physical capital).

Checking Your Understanding

Earlier, the news stories were about:

Improved education in Niger

A new factory opening in Vietnam

A superior business environment in Dubai

A better banking system in the United States Which input to the production function is being increased in each case?

Building on part (b) of Figure 5.3 "A Graphical Illustration of the Aggregate Production Function", draw an aggregate production function that does not exhibit diminishing marginal product of labor.

1.2 Labor in the Aggregate Production Function

Learning Objectives

What determines the amount of labor in the aggregate production function?

What determines the patterns of labor migration?

Why do real wages differ across countries?

The aggregate production function tells how much output we get from the inputs available. Next task: explain how much of each input goes into this function. Begin with labor.

The Labor Market

Figure 5.4 "Equilibrium in the Labor Market" shows supply and demand for labor. The price on the vertical axis is the real wage (nominal wage divided by the price level) — the amount of consumption attainable by selling one hour of time.

Toolkit: Section 16.1 "The Labor Market" and Section 16.5 "Correcting for Inflation" — https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_macroeconomics-theory-through-applications/coopermacro-ch16_s01#coopermacro-ch16_s01 and https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_macroeconomics-theory-through-applications/coopermacro-ch16_s05#coopermacro-ch16_s05

Labor supply curve (upward sloping) — households increasing hours and employment with higher real wages.

Labor demand curve (downward sloping) — firms hire until marginal product of labor equals real wage.

Marginal product of labor depends on other inputs; more capital or human capital shifts labor demand right. The labor market equilibrium determines the real wage and hours of work.

The Mobility of Labor

Wage differences across regions (e.g., US states) induce migration. Example: November 2004 median hourly wage in Florida: $12.50; Washington State: $16.07. Higher wages attract workers, shifting labor supply and equalizing wages until other factors (cost of living, taxes, preferences, cultural barriers) prevent full equalization.

International Migration

Labor moves across countries too, but barriers (legal, cultural, language) are larger than domestic moves. While some movement occurs (e.g., within the EU), most people remain in their birth country. Thus international migration plays a limited role in equalizing wages globally.

Population Growth and Other Demographic Changes

Long-run labor input is affected by population growth, age structure, social norms (women’s labor participation), and public health (e.g., HIV/AIDS impact on working-age population).

Explaining International Differences in the Real Wage

If real wages are higher in country A than country B, the marginal product of labor is higher in A. Reasons:

Hours worked may be fewer in A than in B.

Other inputs (capital, human capital, knowledge, social infrastructure, natural resources) may be larger in A.

Figure 5.7 illustrates these possibilities: lower labor supply or higher labor demand (due to more inputs) can raise real wages.

Key Takeaways

Labor quantity in the aggregate production function is determined by the labor market.

All else equal, labor migrates toward higher real wages.

Differences in real wages across economies reflect differences in the marginal product of labor due to hours worked, technology, and capital stocks.

Checking Your Understanding

To determine patterns of labor migration, should we look at nominal or real wages? Before or after taxes?

Building on Figure 5.7, suppose country A had fewer workers than country B but more capital. Would the real wage be higher or lower in A than B?

1.3 Physical Capital in the Aggregate Production Function

Learning Objectives

What determines the movement of investment in a country?

How does the capital stock of a country change?

What determines the movement of capital across countries?

Analogies with labor: capital stock and utilization rate determine capital input. Capital utilization is how intensively capital is used (e.g., 24/7 operations).

Investment is the addition of new capital goods (factories, machines). In the short run capital stock is fixed; over the long run it changes via investment and depreciation.

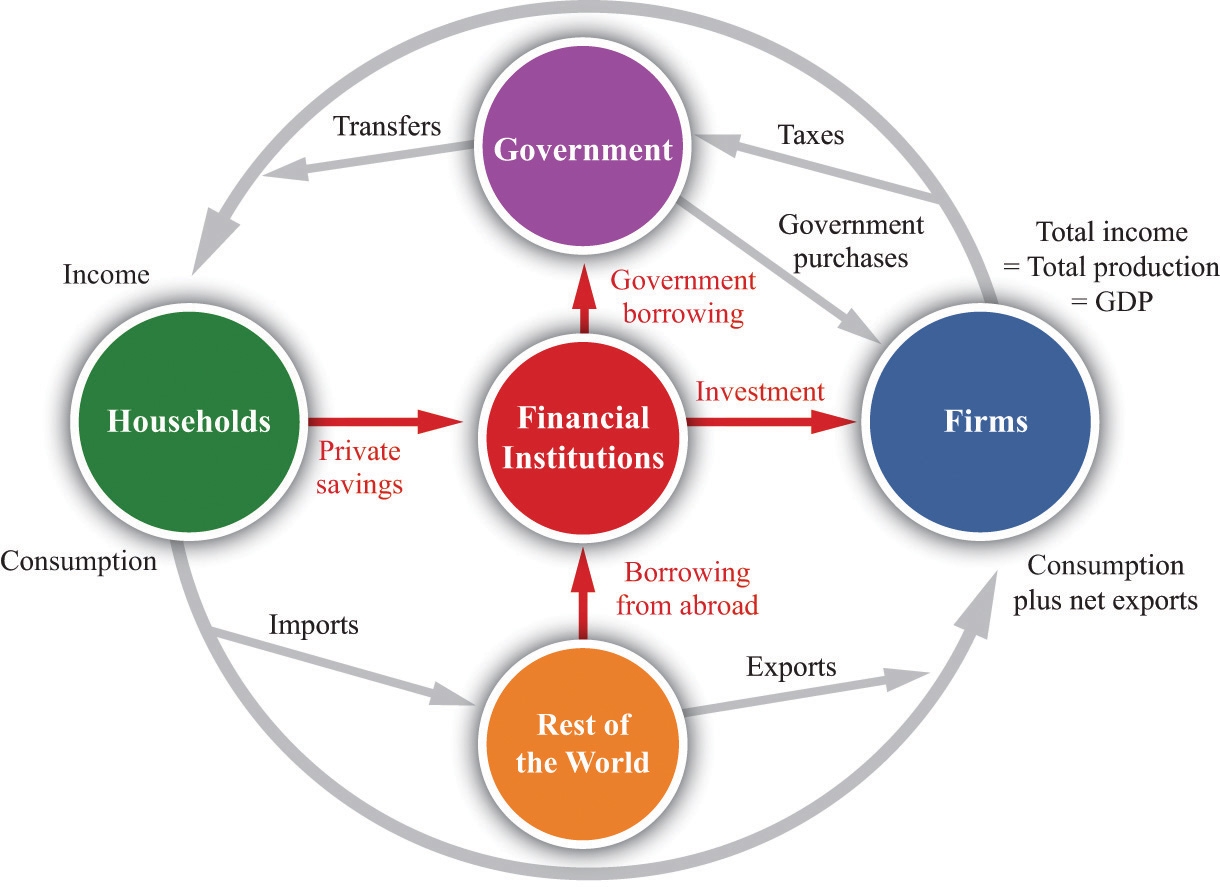

The Circular Flow: The Financial Sector

Figure 1.8 shows four flows in/out of the financial sector:

Households → financial sector: private savings (income saved for future).

Financial sector ↔ government: borrowing/lending depending on deficits/surpluses. National savings = private savings + government surplus (or private savings − government deficit).

Financial sector ↔ foreign sector: net capital flows depend on trade balance; borrowing from abroad when imports > exports.

Financial sector → firms: funds available for investment.

Every flow must balance, yielding: investment = national savings + borrowing from other countries (or = national savings − lending abroad).

Figure 1.8 The Flows In and Out of the Financial Sector

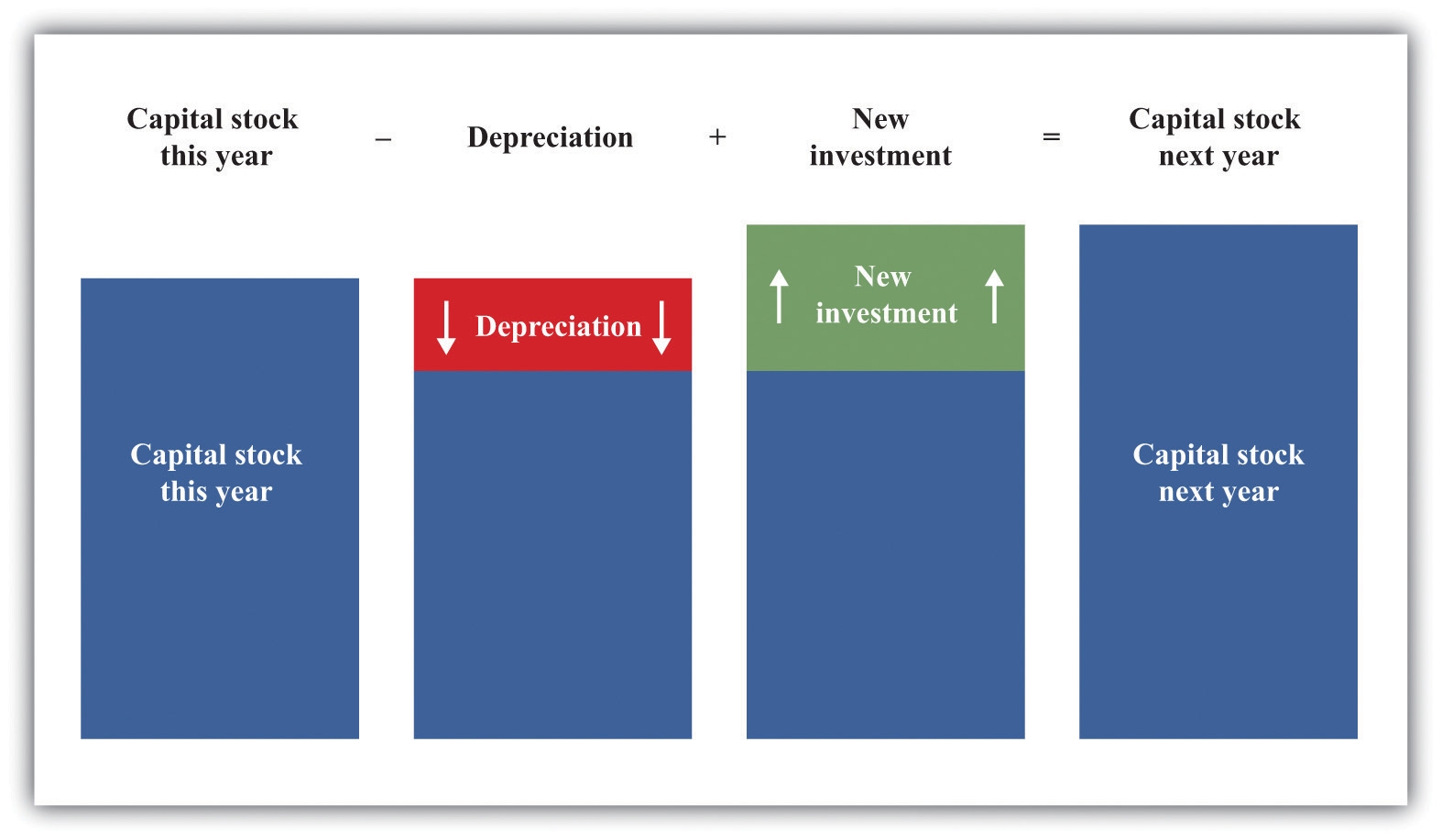

Changes in the Capital Stock

Depreciation: the portion of capital stock lost each year due to wear and tear. Change in capital stock = investment − depreciation.

Figure 5.9 The Accumulation of Capital

Mobility of Capital

Existing capital is often fixed in place, but new capital can be located anywhere. Owners of capital seek the highest real return (marginal product of capital adjusted for depreciation). Two reasons marginal product of capital may be higher in country A than B:

Capital stock is smaller in A (diminishing marginal product).

Other inputs are larger in A (workers more productive).

Capital mobility can cause capital to flow to countries with higher returns, affecting wages: capital inflow raises real wages in recipient country and lowers them where capital leaves. If two countries differ only in capital and labor and capital is perfectly mobile, marginal products of capital and labor will equalize across countries; differences in other inputs (human capital, institutions) can preserve wage differences.

Key Takeaways

Investment = national savings ± borrowing/lending with other countries.

Capital stock changes via investment and depreciation.

Differences in the marginal product of capital drive cross-country capital movements.

Checking Your Understanding

Can investment be negative at a factory? In a country?

Explain how capital movement across two countries affects workers’ real wages.

1.4 Other Inputs in the Aggregate Production Function

Learning Objectives

How does the amount of human capital in a country change over time?

How is knowledge created?

How do property rights influence the aggregate production function?

Human Capital

Education (formal and on-the-job training) accumulates human capital. Individuals and firms invest in human capital, weighing up costs (tuition, foregone earnings) against expected future returns (higher wages). Human capital can depreciate (skills becoming obsolete) and is embodied in people—cannot be sold separately from the person.

Knowledge

Knowledge is created via firm R&D, universities, think tanks, and government-supported research. Knowledge often has two important properties:

Nonrival: one person’s consumption does not prevent others from consuming it.

Often nonexcludable: hard to prevent others from accessing it once produced.

Because creators may not capture all benefits, private incentives to produce knowledge can be insufficient, motivating public support for basic research.

Social Infrastructure

Social infrastructure covers the business environment: property rights, rule of law, corruption, political stability, tax policy, etc. Strong property rights and predictable institutions increase expected returns on investment and thus encourage investment. Poor institutions reduce investment incentives.

Natural Resources

Natural resource availability is largely geographic and depends on extraction technologies and world prices. Resources may be renewable (forests, solar) or nonrenewable (oil, coal). GDP does not account well for depletion of natural resources, so it can misstate long-term welfare if resource stocks are falling.

Key Takeaways

Human capital accumulates via education, training, and immigration.

Knowledge is created through R&D in firms, universities, and public research.

Property rights and institutions significantly influence investment and aggregate production.

Checking Your Understanding

How does on-the-job experience affect human capital?

Why is it difficult to measure a country’s natural resources?

1.5 Globalization and Competitiveness Revisited

Learning Objectives

How is competitiveness measured?

What policies do governments use to influence competitiveness?

Competitiveness: Another Look

Organizations produce rankings of national competitiveness (e.g., IMD World Competitiveness Yearbook; World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness Report). Common themes in measures:

Human capital (tertiary enrollment, skills)

Technology & infrastructure (computers, internet, patents)

Quality of institutions and corruption indicators

Management practices and attitudes

These items correspond to inputs in the aggregate production function. A useful indicator of competitiveness is the marginal product of capital — higher marginal product means more productive investment opportunities and a more attractive place for investment.

Globalization: Another Look

When goods and services are produced and sold, value created equals buyer’s valuation minus seller’s cost. Globalization increases efficiency by:

Allowing goods to go where buyers value them most.

Allowing production where costs are lowest.

Capital and, to a lesser extent, labor mobility further increase global efficiency by allocating capital to higher-return uses.

Concerns and caveats:

There are winners and losers: globalization increases overall efficiency but can hurt some workers and firms.

The global playing field is uneven; developed countries may maintain trade protections while encouraging liberalization elsewhere.

“One size fits all” policy prescriptions may not suit every country; speculative short-term capital flows can destabilize economies.

Most economists see net benefits from globalization but emphasize the need for better management and policies to address distributional consequences and instability.

Policies to Increase Competitiveness and Real Wages

Because increasing labor reduces marginal product of labor and increasing capital reduces marginal product of capital (all else equal), there's a tension between competitiveness and high real wages. However, both competitiveness and real wages can rise together by increasing non-capital inputs:

Invest in education and training to build human capital.

Invest in research and development (R&D) to expand knowledge.

Encourage technology transfer (multinationals, knowledge sharing).

Invest in social infrastructure (rule of law, reduce corruption).

Public policy has a role because knowledge is often nonrival/nonexcludable and private incentives may be insufficient, and because infrastructure/public goods are often provided most efficiently by government.

Key Takeaways

Measures of social infrastructure and human capital are key determinants of competitiveness. Marginal product of capital is a useful competitiveness indicator.

Governments promote competitiveness and wages by building human capital, knowledge, and improving institutions.

Checking Your Understanding

Why is GDP not a good measure of competitiveness?

How could a policy to increase inflow of capital lead to a decrease in competitiveness? What does such inflow do to workers’ real wages?

1.6 End-of-Chapter Material

In Conclusion (brief review of the four opening stories)

Niger: poor due to lack of inputs; World Bank project aims to improve human capital.

Vietnam: multinational investment (e.g., Taiwanese firm) illustrates global capital mobility; capital inflows raise local wages.

United Arab Emirates (Dubai): policy to attract physical and human capital (social infrastructure, amenities).

United States: competitiveness initiatives aimed at education, R&D, entrepreneurship to raise human capital and knowledge.

Key Links

World Economic Forum: http://www.weforum.org

World Competitiveness Yearbook: http://www.imd.ch/wcc

World Bank: http://www.worldbank.org/

Dubai government: http://www.dubaitourism.ae/node

Exercises

Table 1.3 An Example of a Production Function

10

1

1

10

10

20

2

2

10

10

20

4

1

10

10

20

1

4

10

10

30

9

1

10

10

30

1

9

10

10

30

3

3

10

10

40

2

8

10

10

40

8

2

10

10

40

4

4

10

10

40

4

4

20

5

40

4

4

5

20

80

4

4

20

20

By comparing two different rows in the preceding table, show that the marginal product of labor is positive. Make sure you keep all other inputs the same.

By comparing two different rows in the preceding table, show that the marginal product of human capital is positive (keeping other inputs the same).

By comparing two different rows in the preceding table, show that the marginal product of technology is positive.

Does the production function exhibit diminishing marginal product of physical capital?

Does the production function exhibit diminishing marginal product of labor?

(Difficult) Can you guess what mathematical function was used for the production function?

Why are electricians not paid the same amount in Topeka, Kansas, and New York City? Why are electricians not paid the same amount in North Korea and South Korea? Is the explanation the same in both cases?

Think about the production function for the university or college where you are studying. What are the inputs? Classify them as physical capital, human capital, labor, knowledge, natural resources, and social infrastructure.

Suppose government spending is 30, government income from taxes (including transfers) is 50, private saving is 30, and lending to foreign countries is 20. What is national savings? What is investment?

Explain how it is possible for investment to be positive yet for the capital stock to fall from one year to the next.

Is a fireworks display nonrival? Nonexcludable?

Suppose that a country’s capital stock growth rate is 8%, labor hours growth rate 4%, human capital growth rate 2%, technology growth rate 3%, and parameter a = 0.25. What is the output growth rate?

Suppose a country’s capital stock growth rate is 4%, labor hours growth rate 3%, human capital growth rate 1%, output growth rate 5%, and a = 0.5. What is the technology growth rate?

Explain why a decrease in a country’s competitiveness can be a sign that the country is becoming more prosperous.

Would a firm prefer to pay for a general management course or firm-specific software training for an employee? Explain.

Economics Detective Activities

Go to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (http://www.bls.gov). Find the median hourly wage in your state (or a selected state).

How does it compare to the national median?

Which is higher in your state — median or mean wage? Explain.

Find an example of a competitiveness initiative in a country other than the United States. How will the proposed policies help attract capital?

Glossary (selected key terms)

Aggregate production function: A combination of an economy’s physical capital stock, labor hours, human capital, knowledge, natural resources, and social infrastructure that produces output (real GDP).

Real GDP: A measure of production corrected for changes in overall prices.

Physical capital: The total amount of machines and production facilities used in production.

Capital stock: The total amount of physical capital in an economy.

Labor hours: Total hours worked in an economy (number employed × average hours).

Human capital: Skills and knowledge embodied within workers.

Knowledge: The blueprints, information, and technology describing production processes.

Natural resources: Oil, coal, mineral deposits, agricultural and forest lands.

Social infrastructure: The general business climate, legal and institutional environment.

Marginal product: Extra output from one additional unit of an input, holding others fixed.

Marginal product of capital: Extra output from an extra unit of capital.

Marginal product of labor: Extra output from one extra hour of labor.

Globalization: The increasing ability of goods, capital, labor, and information to flow among countries.

Competitiveness: The ability of an economy to attract physical capital.

Labor market: The market bringing together households who supply labor and firms who demand labor.

Real wage: Nominal wage divided by the price level.

Labor supply: The amount of labor households want to sell at a given real wage.

Labor demand: The amount of labor firms want to hire at a given real wage.

Depreciation: The amount of capital stock an economy loses each year due to wear and tear.

Investment: Purchase of new goods that increase capital stock.

National savings: Sum of private saving and government surplus (or private saving − government deficit).

Nonrival good: One person’s consumption does not prevent others from consuming it.

Nonexcludable good: Impossible to selectively deny access.

Property rights: Legal rights to make all decisions regarding the use of a resource.

Renewable resource: Regenerates over time.

Nonrenewable resource: Does not regenerate over time.

Technology transfer: Movement of knowledge and advanced production techniques across borders.

Contributing Authors

This chapter was adapted from Macroeconomics: Theory Through Applications v. 1.0 by Russell Cooper and Andrew John (2012) under the Creative Commons License. The chapter number and chapter title have been changed. The sections on A Numerical Example of a Production Function and Diminishing Marginal Product have been removed. The definition of globalization has been updated. The Accounting for Changes section has been removed. The story about immigration to the UK has been removed (story was pre-Brexit).

Conditions of Use: Creative Commons License

Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

CC BY-NC-SA

Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

CC BY-NC-SA

Last updated